School Project | Tools Used: Solidworks

Why a drawing board?

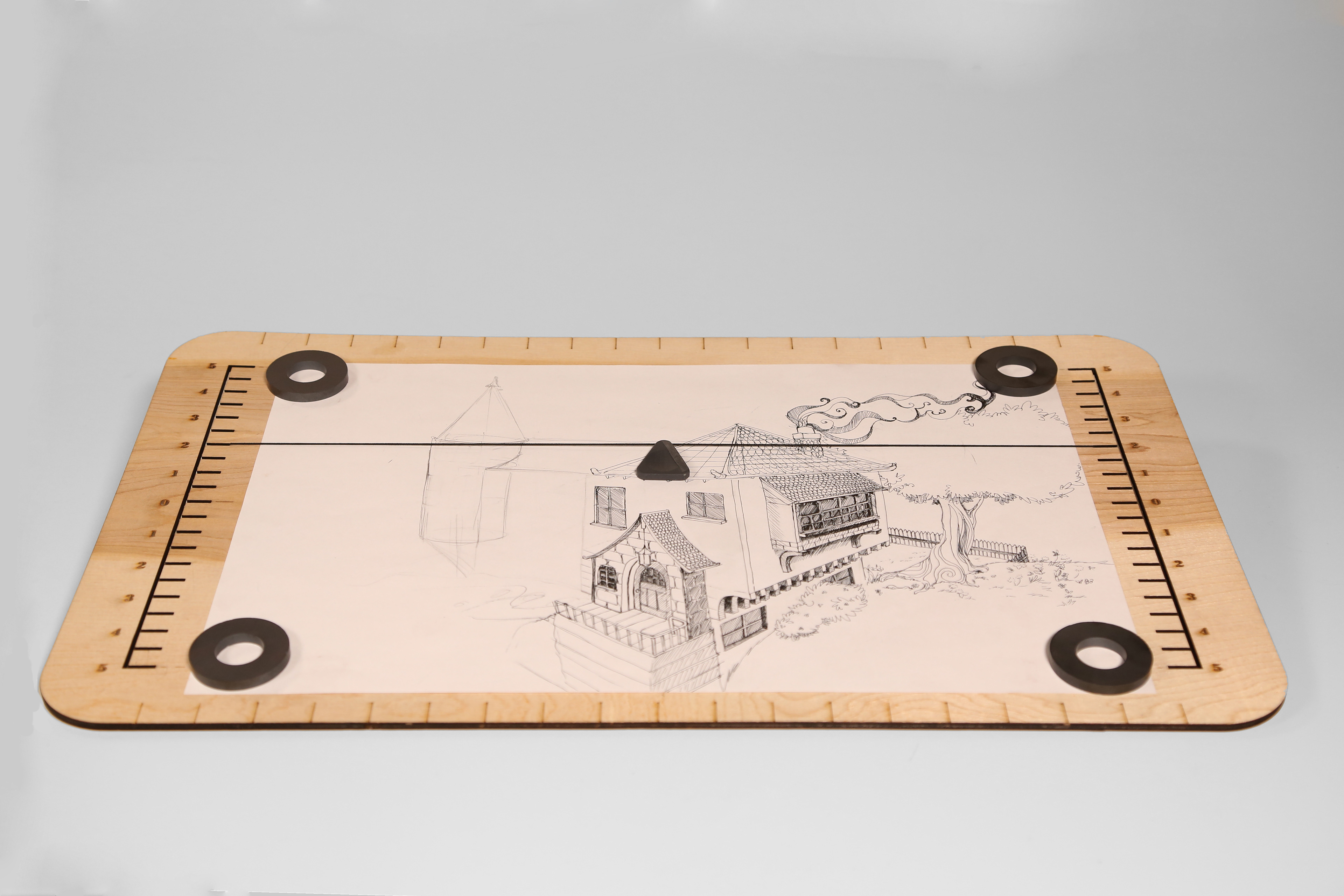

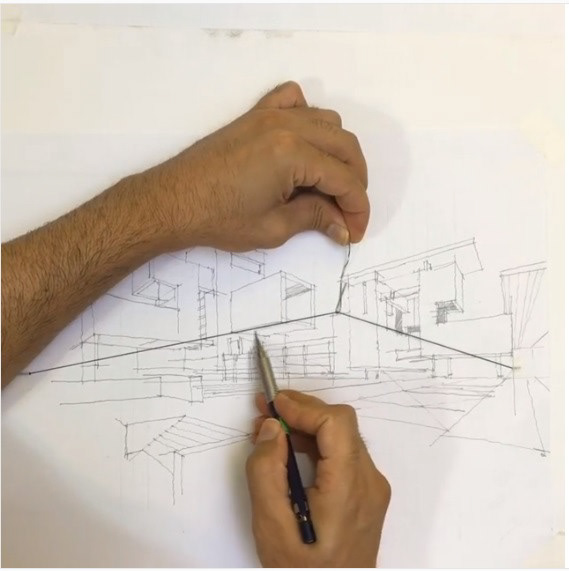

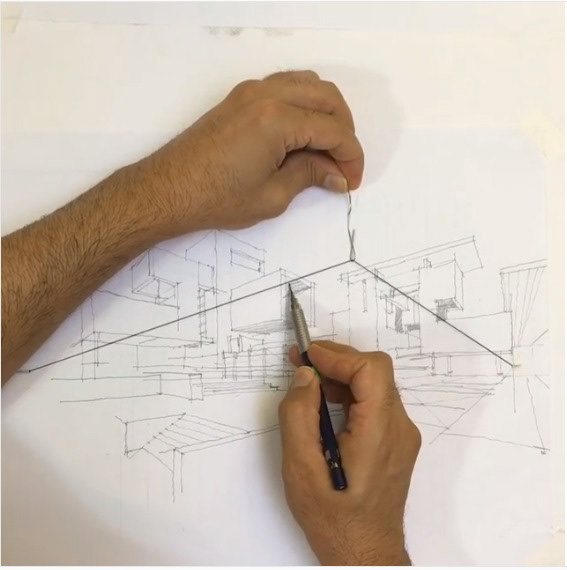

This project started as an assignment in one of my studio courses where the idea was to design a physical product that felt good to use. There weren't many strict guidelines beyond that, besides needing to show progress through prototypes with an emphasis on using feedback from prospective users. My studio partner had a whole page of ideas scribbled out in her notebook, but "perspective drawing lifehack" caught my attention. She then showed me this from the Instagram of architect Reza Asgaripour:

Credit: Reza Asgaripour

Credit: Reza Asgaripour

That day, I learned that apparently drawing in two-point perspective is frustrating, especially for beginning or learning artists that don't get much opportunity to practice drawing in perspective. I didn't know exactly how frustrating this could be for others, on account of pretty much all higher levels of drawing being something I struggle with. More specifically, I just generally suck at drawing overall. Apparently other people share this sentiment about themselves, my studio partner included. This life-hack screamed "this is something worth looking at." Interestingly enough, Asgaripour's life-hack already gave us a pretty solid starting point–by using the string and paperclip to draw in perspective, artists weren't left with messy, confusing sets of guidelines that are traditionally used for perspective drawing forms.

Yeah, I'm really not quite sure what's going on here either.

Our first prototype wasn't pretty, but we needed something for our users to test. And if it's a works-like prototype that doesn't have the most visual appeal compared to other things, that's alright. We just wanted to know if people would even care if this was a problem we tackled, provided the concept even worked to begin with. Apparently the sentiment of "I suck at drawing" was pretty common in our class-bound sample. So onward we go, into the great unknown.

My hastily drawn house in an attempt at two-point perspective. The top house was drawn freehand, without the prototype. The bottom made use of the lifehack, and what a differnce it made.

One of our more artistically inclined classmates drew this one.

The wonders of quick and dirty prototyping never ceases to amaze. Despite the fragile construction, we were able to spend the rest of the studio session going around to fellow students for some initial user feedback. Though our program of study isn't a true design program, we were nonetheless surrounded by fellow students who were aiming to be designers, product engineers, and design thinkers. Any feedback is better than zero feedback. With this early-stage prototype, we got enough feedback from potential users to guide our thoughts as we moved forward with our project.

Development: Cardboard and Paperclip Upgrades

Early feedback was promising, if not a bit focused on the whole problem of "yeah, this thing is made of cardboard which doesn't feel great to draw anything on, really." Barring that focus, we focused on three leverage points that were central to how much our users enjoyed using the drawing board–the board, the elastic "guideline," and the pull implement that manipulated the guidelines. The board itself, initially made of cardboard, was reviewed as "a bit soft." Through a fortunate bit of happenstance, the tables in the class studio were made of a solid slab of finished hard wood–something that our testers made easy comparison to when talking about the actual drawing surface. Other options considered were a metal drawing surface, but some quick A/B testing with users dashed that–the metal just didn't offer the same mix of support and give that hardwood did. Simply put, metal as a backing surface just didn't feel as good.

This is also not my drawing. My studio partner was, and is, much better at drawing than I am.

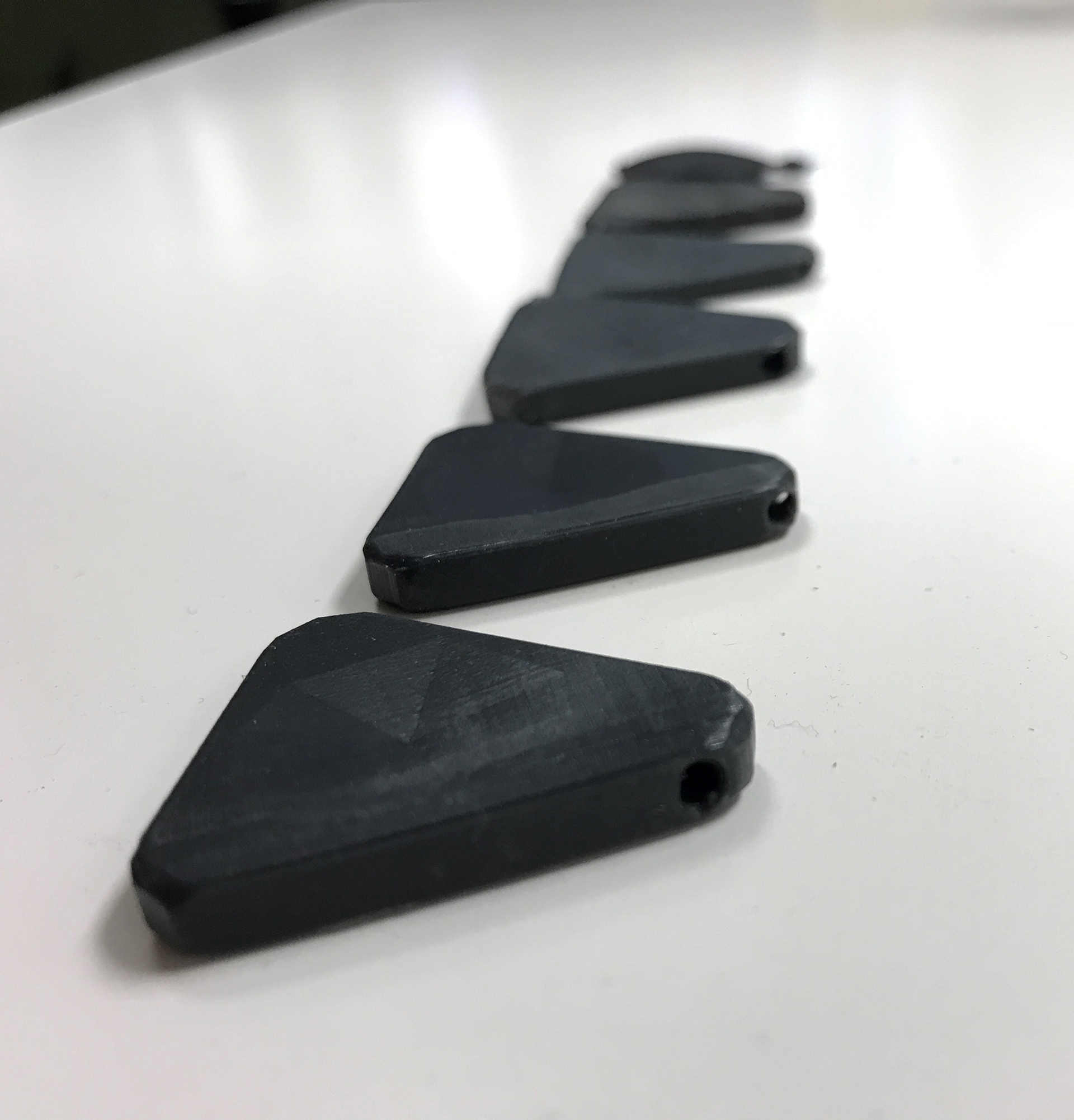

Then there's the matter of what we coined the "pull-tab," along with the guideline. As seen in the picture above, gone were the days of a rubber band and a mangled paperclip. The pull-tab went through a couple of shapes before we settled on the triangular "guitar pick" tab. From user testing, the guitar pick shape felt the most comfortable in hand, with users instinctively pinching it as if holding a guitar pick. It offered enough size and grip to manipulate the guideline while not being hefty or large enough to be "in the way." Each prototype was 3D printed, with the initial versions printed out of PLA. After settling on the shape, I wanted to try out two variants of Formlab's SLA Printer photopolymer resins—rigid and flexible resin options. We settled on the flexible resin material, after some quick A/B testing where we had users pinch, rub, and otherwise handle the pull-tabs in their different materials.

We did similar testing of varying thicknesses in order to find something that our testers felt comfortable pulling and stretching the guideline with. It had to be thick enough that it wouldn't feel like it would break while in use, but still be thin enough to not be too bulky or harder to manipulate. The final pull-tab also had a little divot on either side of the pull-tab surface face that, though nearly imperceptible visually, was easily felt by the thumb or forefinger that guided the hand towards the pinching and pulling positioning that we saw as common across all of our user testers. It was this pinch grip that drove us to the guitar pick shape in the first place.

Pull-tab iterations. I modeled them in SOLIDWORKS, and took advantage of the on-campus 3D printers.

The elastic guidelines were probably the component that gave us the most problem throughout the course of the project. Our user testing for the various materials just ended up with the same sort of feedback. It wasn't "stiff enough to draw straight lines," and anything thicker "started to obstruct the ability to see what [our user testers were] drawing." Due to time constraints in a college course setting, we eventually settled on the 2 mm diameter elastic. It wasn't perfect, with still far too much give to allow for reliably straight lines, but it was the thickest we could get away with without it impacting drawing visibility.

Throughout the search for a "perfect guidelines" material, I jokingly mentioned that a high-tech material that could become be switched between rigid and elastic at will would be amazing—something similar to Batman's cape in Batman Begins. I still maintain that it is the coolest conceptual solution I'd pitched while working on the project, and probably the best unobtainable solution that would have solved all the problems we were having in our attempts to compromise on guideline flexibility vs rigidity.

Final Thoughts: It's not the Final Design

To call our prototype at the end of the studio a "final product" would be a bit misleading—a refined prototype might be more accurate. Do we leave the wood finished or unfinished? What about a metal plate sandwiched between two pieces of hardwood for rigidity? Our refined prototype had a metal plate taped onto the back for the sake of seeing if magnets were a viable way to secure the paper to the board—after all, it wouldn't do for the paper to move on the board while a user is drawing. There were so many more things that needed testing, and not quite enough time or manufacturing skills—or a combination of the two—to allow for further testing before we had to give the project its curtain call for the semester.

This was my first major project where the assignment focus was actually user experience, in the actual sense of "make something enjoyable to use." The project, and the course as a whole, is also probably one of my most formative moments in my journey as a designer. It is, after all, the course that enabled me to discover the sense of enjoyment and discovery that I love so much about design. I believe that working on this project over the course of two months is what awakened me as a designer, pointing my thinking towards user experience as it pertains to experiencing a product. Without user to test what we were making throughout the course of the two months of the project, we would have just been creating in a vacuum—with no idea if what we were doing was headed a remotely good direction.